by Dr. Charles Hoole, Principal, Baldaeus Theological College, February 2003

There are numerous myths surrounding the figure of Arumuka Navalar whose mission

was to revive Hinduism. Myths about his contribution to Christianity has even infected

the church and can be evidenced in the speeches and writings of Christian leaders. Yet

these myths are fictive statements that conceal reality. This letter briefly looks at the real

person of Navalar and his accomplishments.

A reply to a Hindu

Chelvatamby Maniccavasagar's choice of Arumuga Navalar as one of the `Great men that

freed their motherland from British rule' (Daily News, 4 February) is somewhat puzzling.

Navalar's interests were very narrow and sectional, restricted to his own Vellalar caste. It

is no doubt true that during the colonial period `a large mass of people were oppressed

by those who claimed to be superior simply on the basis of birth', but Navalar never

worked against this kind of oppressive system based on birth and privileges. He in fact

worked toward revitalizing the ancient caste system, whose elites saw their power and

privileges grow within the British colonial system.

In his ceaseless missionary activities he aimed to elevate the status of the Vellalars, the

dominant caste in Jaffna. When he began his first school, for instance, all the pupils

enrolled in the first class were from the upper castes: three Brahmans, three Vellalars, and

one Cetty. During the severe famine in 1876, Navalar distributed food only to Vellalars,

and certainly not to the low castes, whose plight under those circumstances would have

been worse than that of others. The food distribution was in line with his teaching in the

fourth Palar Padam, that requires cattiram (gifts, alms) to be given not only to

Brahmans, but to the deserving Vellalar poor as well. Evidently, Navalar was not inclined

towards liberating the oppressed, dalits, on the contrary, his sole concern was to

reify an oppressive caste system.

His activities in the orthodox temples were equally sectarian. The temples that Navalar

chose for his "Prasangams" were all exclusively dedicated to various members

of Siva's family. He would not tolerate rivals competing for devotees; thus he launched a

successful crusade against the goddess Pattini/Kannaki. By claiming that she was an

heretical Jain goddess, he managed to banish her from the Jaffna soil. In the temples he

aimed his teaching and preaching at people of `respectable' family and caste. His

intention was, in part, to acquaint them with a strictly textual religion so that they may be

enabled to fulfil their ritual/caste duties correctly and be proper Saivites. Navalar of

course was not blindly reasserting a traditional religion. In a carefully worked out strategy

he was advancing certain claims on behalf of his own Vellalar caste, with the aim of

upward mobility. Traditionally Vellalars were regarded as Sudras in the varna

order, however, owing to their historic alliance with the Brahmans their status had

remained somewhat anomalous. Navalar however attempted to elevate their ritual status

by ascribing to them the right to wear the Punul and the right to read the Vedas.

Implicitly, therefore, he did elevate them to the status of the twice-born. This is, of

course, a well known `brahmanical' device used by the lower castes to climb the social

ladder within the varna order, but this kind of pursuit had little to do with the

struggle for equality, dignity and freedom!

Chelvatamby Maniccavasagar's short account of Navalar exhibits a few glaring errors.

Arumuka Navalar was born in 1822, not 1882 and died in 1879. Also it is very

misleading to state that he "translated the Bible into Tamil at the request of Rev. Peter

Percival". This statement can imply that Navalar was solely responsible for translating the

Bible and that he was the first to do so, infact, such claims are widespread. Unfortunately

these claimants are ignorant of the history of Tamil Bible translation.

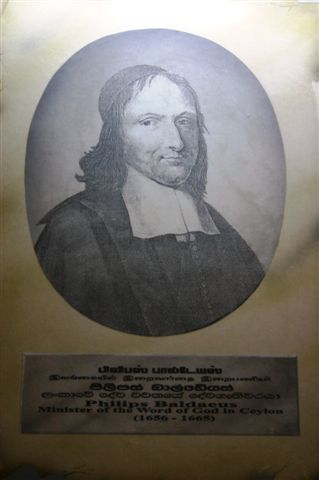

Even before Navalar became associated with Bible translation there were already two

Tamil translations in the market, that of Philip Fabricius (1710-1791) and C. T. E.

Rhenius (1790 - 1838). These translations had their precedents in the works of Phillipus

Baldaeus (1632 - 1671) and Bartholomeus Ziegenbalg (1682 - 1719). Based in Jaffna,

the Dutch Predikaant, Baldaeus broke new ground when he translated the gospel of

Matthew into Tamil by 1660. A few decades later in Tranquebar, south of Madras,

German missionary Ziegenbalg, had translated the entire New Testament into Tamil by

March , 1710. When both of them began their work there was no Tmail prose work which

could be used as a standard to guide them. Certainly there was plenty of Tamil poetry but

it was very different from the every-day language of the people. Their successors, Adrian

de Mey of Nallur, Jaffna and Benjamin Schultze of Tranquebar were then able to build on

the work of these two pioneer translators.

Even before Navalar became associated with Bible translation there were already two

Tamil translations in the market, that of Philip Fabricius (1710-1791) and C. T. E.

Rhenius (1790 - 1838). These translations had their precedents in the works of Phillipus

Baldaeus (1632 - 1671) and Bartholomeus Ziegenbalg (1682 - 1719). Based in Jaffna,

the Dutch Predikaant, Baldaeus broke new ground when he translated the gospel of

Matthew into Tamil by 1660. A few decades later in Tranquebar, south of Madras,

German missionary Ziegenbalg, had translated the entire New Testament into Tamil by

March , 1710. When both of them began their work there was no Tmail prose work which

could be used as a standard to guide them. Certainly there was plenty of Tamil poetry but

it was very different from the every-day language of the people. Their successors, Adrian

de Mey of Nallur, Jaffna and Benjamin Schultze of Tranquebar were then able to build on

the work of these two pioneer translators.

The translation of Fabricius, the "Golden Version" is no doubt the most famous. He was a

saintly and devoted German missionary, whose New Testament was published in 1772

and Old Testment in 1791. He translated from the original Greek and Hebrew texts, and

his version's faithfulness to the originals has commanded the respect of all subsequent

translators. Although he never lived to see it, Fabricius' version of the Bible was revised

and printed in 1796. Later, the Madras Bible Society published the same version in 1824.

Hence it is not surprising that Fabricius' translation is now the real base of the Tamil

Bible which is now widely in use.

So in what sense did Navalar contribute to Bible translation? The Tentative Version of

the Bible or the Jaffna Version associated with Navalar was produced in 1850 by the

Jaffna Bible Society. It was however rejected by the Bible Society of Madras on the

grounds that it was too heavily loaded with Sanskrit words and that it did not stick closely

to the originals. More importantly it departed too much from the standardized "Christian

Tamil" of the Fabricius version, hence the regular users were unlikely to endorse it. The

result is that the Jaffna Version never reached the market; and another version based on

Fabricius was produced in 1871 by Rev. Bower assisted by poet Krishnapillai.

All this means that Maniccavasagar is referring to a version of the Bible that hardly

anyone could have seen or used in the history of Tamil Christianity. In any case that

particular version could never be the product of Navalar alone. The fact is, he simply did

not know Greek, Hebrew, or Latin, the languages of the original text - whose exact

meaning the translator had to discover before rendering it into Tamil. The Jaffna Version

was translated by a six member committee, headed by Peter Percival, Principal of Central

School. Jaffna at that time had a tremendous fund of scholarship from which to draw,

both on the side of Western missionaries as well as on that of Jaffna Tamils. Among the

American missionaries were Levi Spaulding, H. R. Hoisington, Samuel Hutchings,

Daniel Poor and Miron Winslow. Two Tamil pundits, Arumuka Navalar and Elijah Hoole

were enlisted by Percival to help with the style, while the missionary scholars took final

responsibility for the version's accuracy.

Under these circumstances it would be an exaggeration to claim that Navalar translated

even this extinct version of the Tamil Bible. As Percival's assistant he worked under the

guidance and supervision of a team of eminent missionary scholars. With Elijah Hoole,

he no doubt helped the missionaries to purify the idiom and polish the language, but

Navalar could hardly be considered as a major contributor to this translation work. The

Jaffna Version was a product of a committee, whose chairman was Peter Percival, hence

it would be more accurate to associate this translation with his name.

The above account shows that it has now become virtually impossible to know the

Navalar of history. Virtually every significant development in the nineteenth century,

actual or imagined, is being attributed to him by his biographers. In the Geertzian sense,

whatever Navalar originally was or did as an actual person, has long since been dissolved

into an image. The image of Navalar as a social reformer, religious revivalist and a great

national leader is so well established in people's minds that it is virtually impossible to

distinguish fact from fiction or myth from reality.

Dr. Charles R. A. Hoole

Principal, Baldaeus Theological College

Trincomalee

|

|

|

|